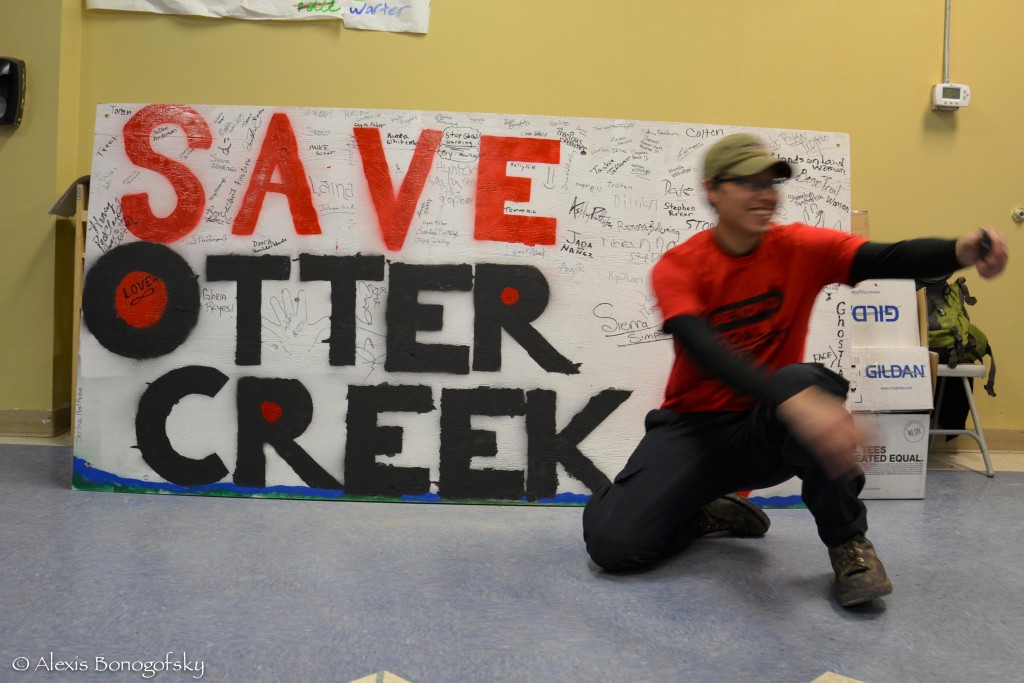

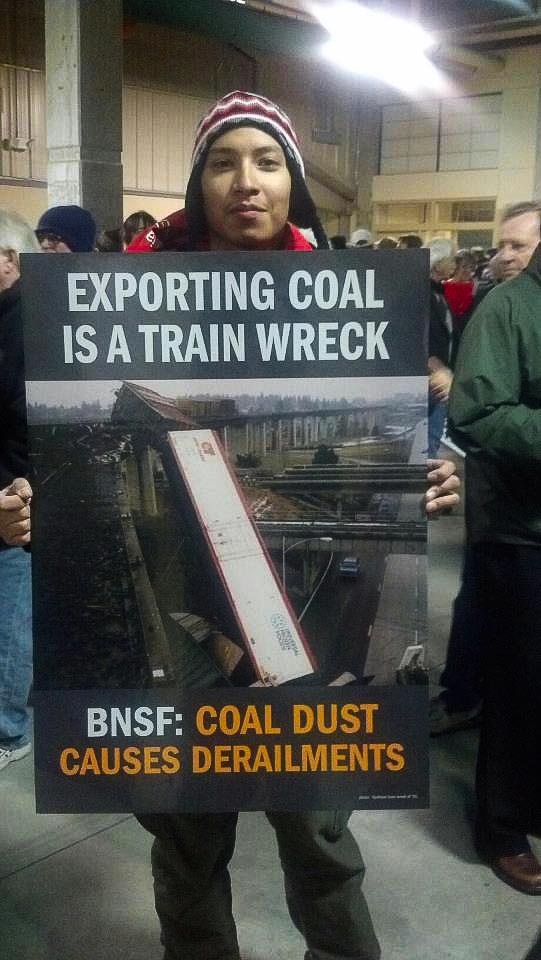

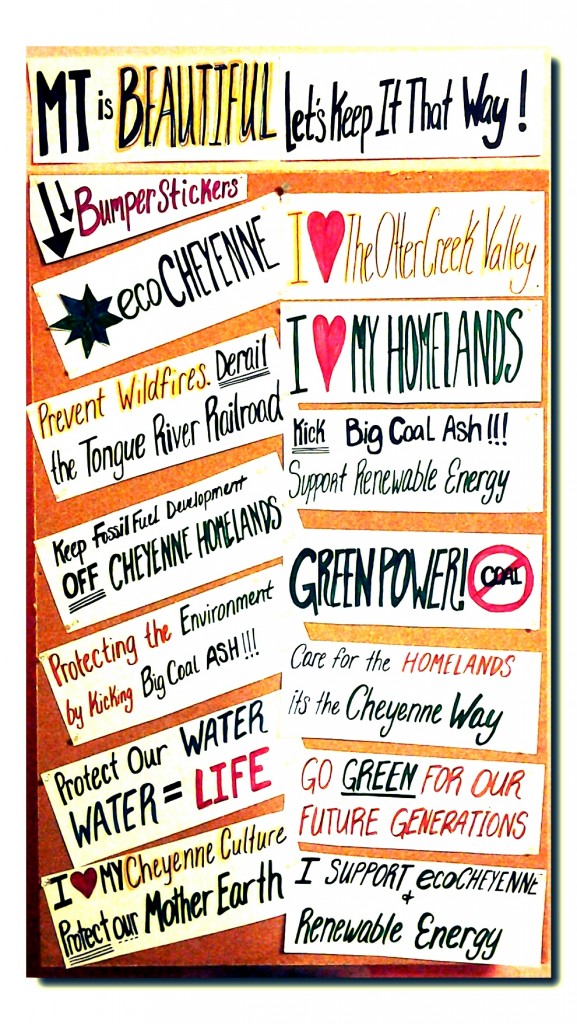

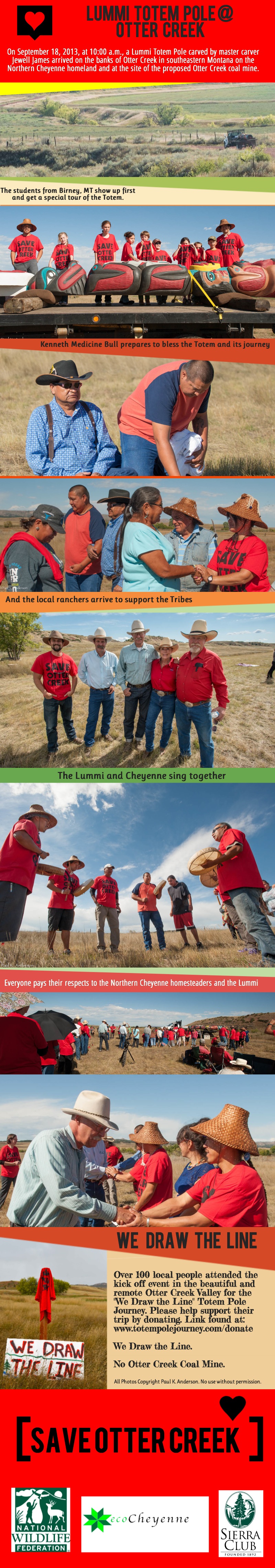

2013 was a good year. People from Montana, South Dakota, North Dakota, Wyoming, Idaho, Washington, Oregon and countless other states came together for events, public hearings and community gatherings to help stop the proposed Otter Creek coal mine and Tongue River Railroad in southeastern Montana. I’ve pulled together some photos that exhibit the depth of the love that people have for southeastern Montana and some of the amazing moments of the last year. Thanks to Beth Raboin, Paul K. Anderson, Janis Spear and Vanessa Braided Hair for their photos of some critical moments.

I start in January during the public hearings over the proposed Otter Creek mine, then the Inter-Tribal No Coal Gathering in Lame Deer in March and then on to the Section 106 Tribal Historic Consultation meetings where we toured the proposed Tongue River Railroad route. Then we move into the summer for renewable energy trainings, education booths at pow-wows and finish with the Lummi Totem Pole Journey in the fall. If you need some background on our fight to stop the mine and railroad, please check out my NWF blog by clicking here.

Enjoy!

The other day, I was splitting wood for winter. I couldn’t hear much over the sounds of the splitter or my ear protection so I was startled when I looked up and there was an old green Ford pickup parked right next to me.

A random guy: “You in charge here?”

Me: (5 second hesitation) “Why?”

I’ll stop the story here and tell you that “why” is my standard answer for three questions I’m frequently asked: Am I in charge? Am I Tom’s daughter? And, are those your goats? Never say yes right away.

Man:“Well, I was wonderin’ if those goats I see when I drive by are your goats, I’m a bus driver and man they’re good lookin’ goats and I have goats too but I’ll be goddamned if my Pygmy buck can’t get himself up on my Boer doe to get ‘er done and well you got those good lookin’ Boer goats and I got to thinkin’ I could bring my doe down to your place and one of your bucks could knock her up and what do you charge for something like that?

Me: “Ummm”

If you’ve never had the pleasure of seeing a goat buck in rut, then you’re missing out on one of the most disgusting and fascinating displays of male sexuality that exists on this planet. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

A goat buck in rut is stinky and horny and angry. The first time I smelled a buck in rut, I threw up a little bit in my mouth. Fortunately, seven years later, I can’t smell it anymore because my olfactory senses are traumatized and shut down.

And, they are horny. Horny like you’ve never seen. They are angry if they don’t get what they want. If you are an intelligent being you would never put yourself between a rutting buck and a doe in heat.

The buck urinates on his belly, his face, his beard and his front legs. Yum. And then he lifts his upper lip in order to detect pheromones that the doe is putting off to let him know she is in heat.

[Enter, the doe in heat]

She walks toward the buck, she sways her hips, and then squats and urinates. He places his nose in the urine stream. Oh yeah. Then, he follows her around, kicking out one of his front legs in a rigid duck step letting out a weird barking sound. If she’s really into it she rubs herself up against him.

The goat buck then gives himself a blow job and ejaculates on his face and stomach and beard. It’s all part of the courtship. After he is covered in semen and urine, he mounts the doe to finish his business. You know it hit the spot when she thrusts her hips forward. Mark it on the calendar; a baby goat will be born five months later.

Makes you wonder, about a lot of things, doesn’t it?

Let’s return to the opening scene: me, cutting wood and listening to a nice old man ask me how much I would charge for my goat buck to knock up his does.

Random Guy: So…how much?

Me: (silence)

Him: “You in charge?”

Me: “Nope, I just work here.” (I turn and point to Mike, who is walking up from the bottom pastures)

Me: “That guy, that guy’s in charge.”

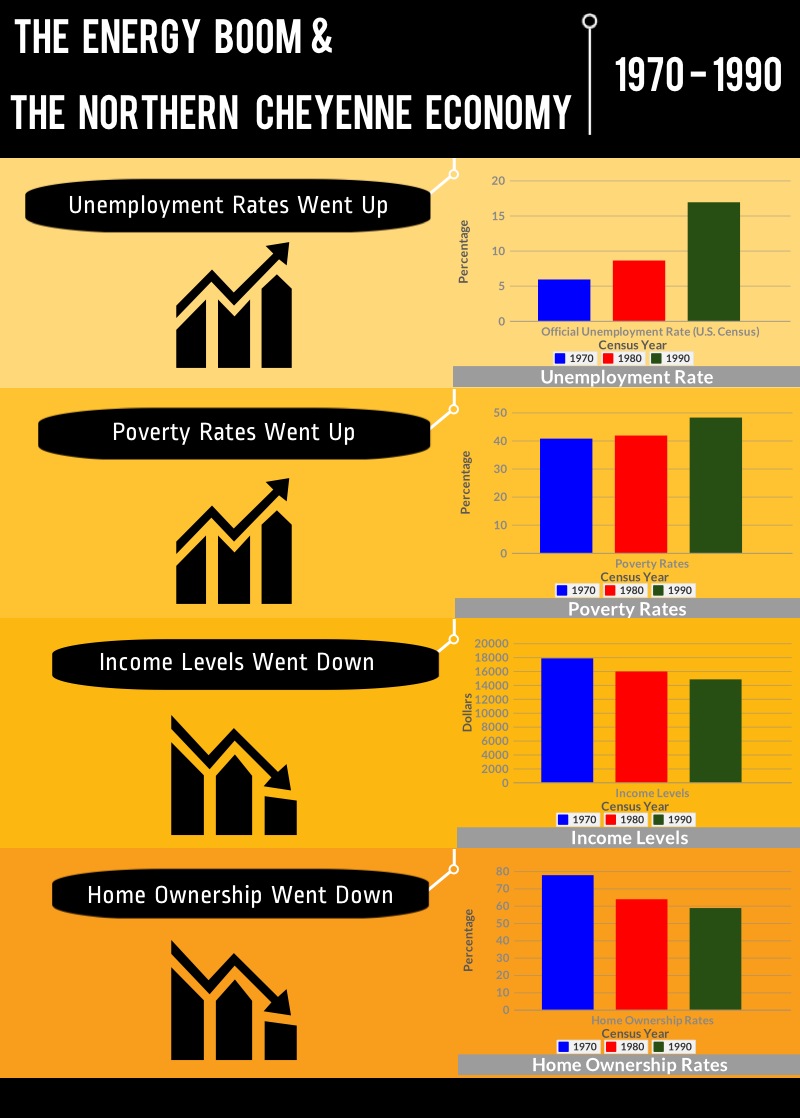

“But we all know how it goes. You guys move in, one side benefits and the other side doesn’t.” Northern Cheyenne tribal member, Otter Creek Scoping Hearing, February 2013

Back in the 1970’s and 1980’s, things were booming down in southeastern Montana. The Colstrip coal plant was under construction, coal mines were being dug, oil was being drilled.

But things weren’t booming for everyone. Yes, local, state and federal governments raked in tax revenues and royalties. Traveling workers were brought in for construction jobs. Money was filling the coffers of some of the biggest corporations in the country.

But that money never reached the Northern Cheyenne Tribe or its citizens. The truth is that despite the major energy development that was happening near the Northern Cheyenne Reservation, economic conditions got worse, both in absolute and relative terms. The mineral wealth created did NOT flow to the residents of the Northern Cheyenne Reservation.

This startling fact was the conclusion that economic and social researchers from the Northern Cheyenne Tribe and various universities found in their 2002 Report to the Bureau of Land Management.* [To download the relevant chapter of the report, please click on this link Northern Cheyenne Economic Study.] These researchers also believe they found the reason why the boom hurt instead of helped the economic, social and environmental conditions on the Reservation.

Why is what happened in the 70s and 80s relevant today? Because the circumstances that contributed to the decline in economic conditions on the Reservation during the boom have not changed and are not likely to change anytime soon.

Unfortunately, we can predict with a high level of certainty that if the Otter Creek Mine and Tongue River Railroad are built, it will hurt an already struggling Reservation economy.

During the Energy Boom Economic Conditions Deteriorated on the Reservation

In the report that I mentioned above, they explored the impacts of the energy boom on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation. What they found was startling.

- The unemployment rate tripled

- The poverty rate increased 10%

- Home ownership rates dropped 20%.

- Median Income levels fell 17% while income levels off the reservation doubled.

- Already stressed social services and economic resources on the reservation became even more strained.

Researchers found that these deteriorating economic conditions could be attributed directly to the boom. So, now the question is, why?

Why Didn’t the Tribe Benefit from the Boom?

The report stated four major reasons why the Tribe did not benefit from this boom and actually suffered from it, economically, socially and environmentally.

- The lack of access of Northern Cheyenne to highly paid energy jobs:

During the boom, tribal members were able to secure around 3-8% of the energy related jobs even though the tribal members were about 1/3 of the working age population in Rosebud County. This had nothing to do with educational levels. The education levels of Northern Cheyenne were almost equal to that of non-Indians in Rosebud County. Therefore, a majority of the positive impacts from the boom through wages completely bypassed the Reservation.

- The limited local commercial infrastructure on the Reservation:

If the workers in these energy jobs had spent their money on the Reservation, that would have benefited the local businesses and therefore benefited the local economy. However, workers took their paychecks and spent them in places like Colstrip or Billings. No money flowed to tribal businesses. The Reservation did not have a local economy in place to derive the benefits from that extra money. Colstrip and other urban economies like Billings expanded because of the new dollars. That expansion, in turn, took even more dollars away from the Reservation because Reservation residents also took advantage of the increased services and goods in Billings and other growing towns. Rather than gain from increased levels of income and expenditure, the Reservation economy shrunk.

- The Tribal government had no access to mineral revenue to support public services and infrastructure on the Reservation:

This is a big one. Rosebud County, the city of Colstrip, the state of Montana and the Federal Government were all beneficiaries of a significant amount of energy related revenues through mineral taxation and the sharing of royalty revenues. These governments could use those mineral revenues to expand the services provided to citizens and businesses, improve schools and other public facilities and finance various economic development and citizen support programs. The Northern Cheyenne Tribal Government did not have access to a share of those mineral revenues but had all of the same infrastructure, social and environmental impacts from the development. While other governments were able to use the money to improve their cities and towns the Northern Cheyenne could not do the same. Steps that the Tribal Government could have taken to increase the likelihood that some of the benefits associated with the energy boom would have reached their community could not be funded.

- The impact of the Northern Cheyenne commitment to place:

The report stated,

“To the Northern Cheyenne the Reservation is not just a convenient location temporarily chosen because of the economic opportunities in the area, but the Tribe’s permanent homeland. Tribal members over many generations have contributed substantial resources to the integrity and protection of their homeland. This commitment to place can be contrasted with the large, mobile, workforce that helped construct the coal mines, the Colstrip power plants and the oil fields. Those workers came for well-paid jobs that were available and when those jobs ended, they traveled on to other places in the pursuit of new economic opportunities. For the Northern Cheyenne, leaving the area is not usually an acceptable solution. The Northern Cheyenne are committed to making the Reservation a viable homeland for their people, economically as well as culturally, socially and environmentally.

The Economic Impacts of the Proposed Otter Creek Mine and Tongue River Railroad on the Northern Cheyenne Tribe: What has changed?

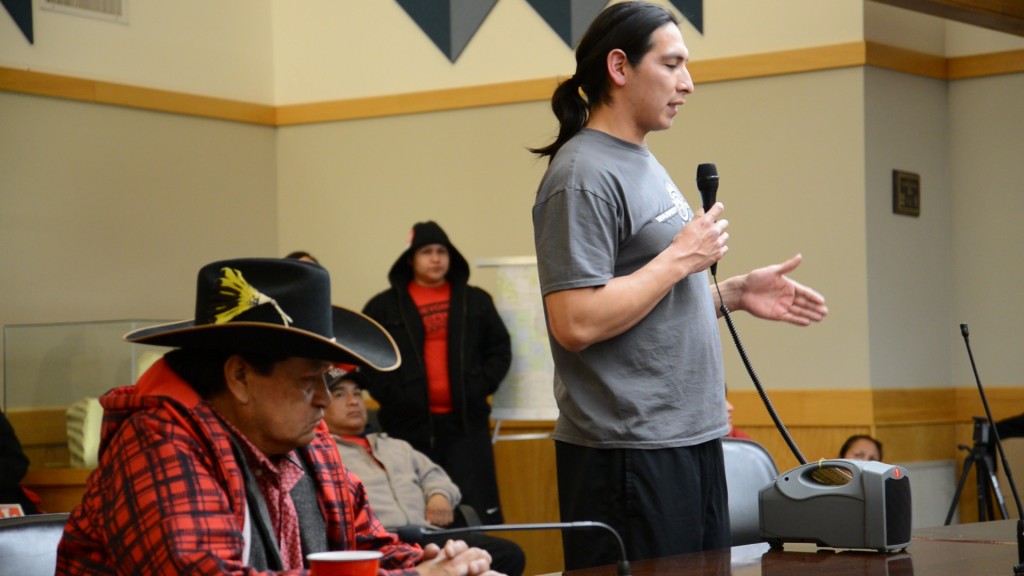

At the public scoping hearing held in Lame Deer in February of 2013, a young Northern Cheyenne man who had, for a short time, worked in a nearby coal mine, stated,

“But we all know how it goes. You guys move in, one side benefits and the other side doesn’t.”

What this young man said is exactly what happened in the 1970s and the 1980s to the Cheyenne people. The researchers state very clearly,

“Because Northern Cheyenne Reservation poverty is not so much a condition as a process or structural relationship between the Reservation and surrounding region, it tends to shape new development initiatives rather than being changed by them. This means that new development initiatives within the region, in the absence of conscious intervention, become part of this existing dynamic relationship and may tend to worsen rather than alleviate the poverty-stricken position of the Reservation.”

And now here we are at the brink of another massive energy development project to the east of the Northern Cheyenne Reservation.

And not one of those four conditions have changed since the first energy boom.

And not only has nothing changed, the money that the Northern Cheyenne were promised by the state of Montana in the 2002 Otter Creek Settlement Agreement to deal with impacts from this development have never been secured.

“Federal legislation will be sought which will: (a) provide federal funding to the Tribe for Reservation public services and facilities; (b) provide federal funding for certain Tribal cultural activities relating to Otter Creek and the surrounding area; and (c) rectify a claimed 100-year old federal error which deprived the Tribe of ownership of 8 ½ sections of Reservation subsurface.” (Exhibit C, Otter Creek Northern Cheyenne Settlement Agreement)

Guess how many of those have happened?

If you guessed zero, you guessed right.

And, as a side note, don’t you love that instead of the coal company paying for infrastructure and public service needs that will be created by their mine, taxpayers are expected to pick up the bill?

Learning From The Past

The coal companies and the state of Montana come to southeastern Montana with promises of economic development and prosperity. They say that this coal mine and the railroad will provide much needed jobs for Reservation residents. They say there will be employment programs but leave out that there will be no hiring preference or quotas and therefore no real way to hold the companies accountable. They say it will bring prosperity to a struggling rural economy.

But what they don’t tell you, what they don’t want people to know, is that it will hurt the people who are least equipped to deal with the impacts. It will hurt the already struggling economy on the Reservation. It will degrade water quality in the Tongue River, a river that people depend on for food and water. It will cause air pollution in Ashland, Lame Deer and Birney, causing increase in asthma, cancer, heart disease and other illnesses. It will bring in more drugs and social problems, causing a strain on the communities and social services.

And there will be no one there to pick up the pieces because Arch Coal is just there to open a coal mine, and nothing else.

Please send me a message if you would like the entire report by the Northern Cheyenne Tribe to the BLM and state of Montana. It is an extremely large file. However, you can download Chapter 3, detailing the impacts of the boom on the Northern Cheyenne Tribe by clicking here.

* To download a list of the report’s authors and researchers, please click here.

During the 2011 Exxon oil spill on the Yellowstone River, I was simultaneously told by our public health officials and Exxon that the oil covering my farm was not dangerous to my health but I should stay away from the oil. Two days after the spill I went to the hospital with nausea, headache, fatigue, dizziness and all that good stuff that comes along with inhaling hydrocarbons.

When coal mines use explosives to loosen up coal seams in coal mines, sometimes a nitric oxide orange cloud forms. They tell residents that this cloud is not poisonous but make sure to stay inside.

Government and corporations do this a lot. It is the epitome of Orwellian double speak. Make a statement with the message that you want the public to hear (“It’s safe”) and then immediately negate that to cover your bases (“but stay away from it”).

How does this relate to the Tongue River Railroad?

A couple of weeks ago, I heard that the draft EIS for the Tongue River Railroad was delayed so I called the Surface Transportation Board (STB) to confirm. The staff told me over the phone, verbatim, that “the Tongue River Railroad Company has asked us to defer work on the draft EIS due to a budget crunch.”

The definition of defer is “to put off (an action or event) to a later time; postpone.” The definition of a budget crunch is “a situation that arises because of a shortage of money.”

Ok, got it. The Tongue River Railroad company (TRRC) is delaying work on the draft EIS because they don’t have enough money to finish the draft EIS on the original timeline. I don’t think that there are too many ways to interpret that statement.

But ever since the Great Falls Tribune reported that the railroad study would be delayed until 2014 due to the budget crunch, both the STB and TRRC have been back pedaling trying to explain that yes, there is a delay and yes, it is due to budget issues and yes, some work is being postponed but no, nothing has changed and no, it isn’t because TRRC doesn’t have enough money and no, the work isn’t stopping.

Well, what is it? It can’t be both.

Don’t misapprehend me

Today, on the Section 106 consultation call (if you don’t know what Section 106 is, google it) David Coburn, the attorney representing TRRC stated that there is, “No question about TRR financing or commitment to the project. I don’t want this to become a misapprehension of people on the call.”

I found this statement amusing since TRRC has been trying to get this rail line built for about 30 years. I don’t think the revised timeline shows a lack of commitment but it does show a lack of financing, market and support. They’ve spent 30 years wasting people’s time, money and energy, 30 years of coming up with various schemes to get it built and 30 years of this project hanging over the heads of the people who care about the Tongue River valley.

But don’t misapprehend me, David, I believe the commitment is there, especially among the backers of this project. I’m sure it’s easy to support a project when you don’t have to deal with any of the direct environmental, social or cultural impacts.

I often think about the how many hours people have spent fighting this railroad and how their lives may have been different if they didn’t have this hanging over their heads for 30 years. Who knows how their lives would be different. Maybe less stress, less heart attacks, maybe more children…who knows?

I asked a friend who has fought this railroad for 30 years how much time he thought he had spent reading documents, going to public hearings, writing comments, worrying, talking to neighbors, driving to meetings etc.

He laughed.

I think he probably had to laugh or otherwise he might cry.

Where does that leave us?

This is where I’m going to lose some of you folks who aren’t into the details of this project but I hope that those of you who were on the Section 106 call will keep reading because I think we all left feeling a little confused. I have a couple of questions that would be nice to have answered by the STB. If you have questions you’d like answered shoot me an email or post a comment. It might be worth having Q & A call with the folks at the STB.

- What exact work is being delayed till 2014? And I don’t mean this in a vague way that would lead to an answer like, “well, some of the writing of the EIS is delayed.” I would like a detailed list of the exact activities of staff from STB and ICF International that is not going to happen until 2014.

- If the TRRC has the money like they say they do, why don’t they increase the budget and get it done on the original timeline? Why wait till 2014? It seems that the three owners of TRRC, (owned by billionaire Forrest Mars, Burlington Northern Santa Fe and Arch Coal) could scrape up the cash to finish it.

- What was the budget for the development of the draft EIS and what is the new budget? When will we know when TRRC has the money for it?

- Does the TRRC pick up all costs for this work or are taxpayers paying for some of it? On the Section 106 call today, an STB staffer said, “we would love to do another face to face meeting but the budget is not there.” Then she said she was talking about the federal budget. Does this mean that STB has to pay for their own expenses when they are working on TRR studies? I thought the railroad company was paying for all expenses associated with the EIS and Section 106 process.

- How, in detail, is the STB coordinating work with the State of Montana on the cultural and environmental studies in the Otter Creek valley? The Tongue River Railroad and Otter Creek coal mine are the same project even though they are being permitted by separate agencies.

- During the in-person Section 106 meeting, the Tribes present stated they wanted to do a TCP study of the entire area. Is this option still on the table?