If you lived in Montana in the 1980’s, chances are you owned a three-wheeler or had friends who owned three-wheelers. We had a couple three-wheelers and my Grandpa Frank bought my sister and I a kid’s three-wheeler.

Yes, you read correctly. They made three-wheelers for children.

This was a bad idea.

Driving three wheelers without helmets.

Bad idea.

Wearing shorts while driving said three-wheeler.

Bad idea.

We tipped it over too many times to count. Somehow we are both still alive.

Once upon a mine, in a land far, far away, called Canada, a big mining company named Noranda started a small mining company called Crown Butte Mines.

Crown Butte wanted to mine deep into the Beartooth Mountains in Montana for gold, silver and copper. But the place they wanted to mine was special to people and right next to Yellowstone National Park. The People became very angry.

Then it went a little something like this.*

Once Upon A Mine: Act I

[Enter The People and President Bill Clinton]The People: No. And by no we mean hell no.

President Bill Clinton: Oh, really? Is that not cool?

The People: Not cool.

President Bill Clinton: You’re right. Yellowstone National Park is too important. All the wildlife, the water….I get it. We should stop that from happening. I’ll take care of it.

The People: Cool.

Years pass. Lawsuits are filed. People are organized. The Clinton Administration goes into long negotiations with the mining company. Finally, an agreement is reached and the Federal government agrees to give Crown Butte $65 million dollars worth of land and minerals and cash in exchange for the divestiture of Crown Butte’s interest in the mine site.

President Bill Clinton: Success! I saved Yellowstone National Park! That should make me very popular with the ladies.

[Montana Governor Marc Racicot enters the stage from the back.]Montana Governor Marc Racicot: Hey! Clinton! Stay out of our business, we need that tax revenue!! And jobs!!!

[The entire Department of Interior sighs heavily at the same moment which leads to a split second increase in the amount of carbon in the atmosphere in Washington D.C., contributing to climate change.]President Bill Clinton: Fine. How about $10 million dollars?

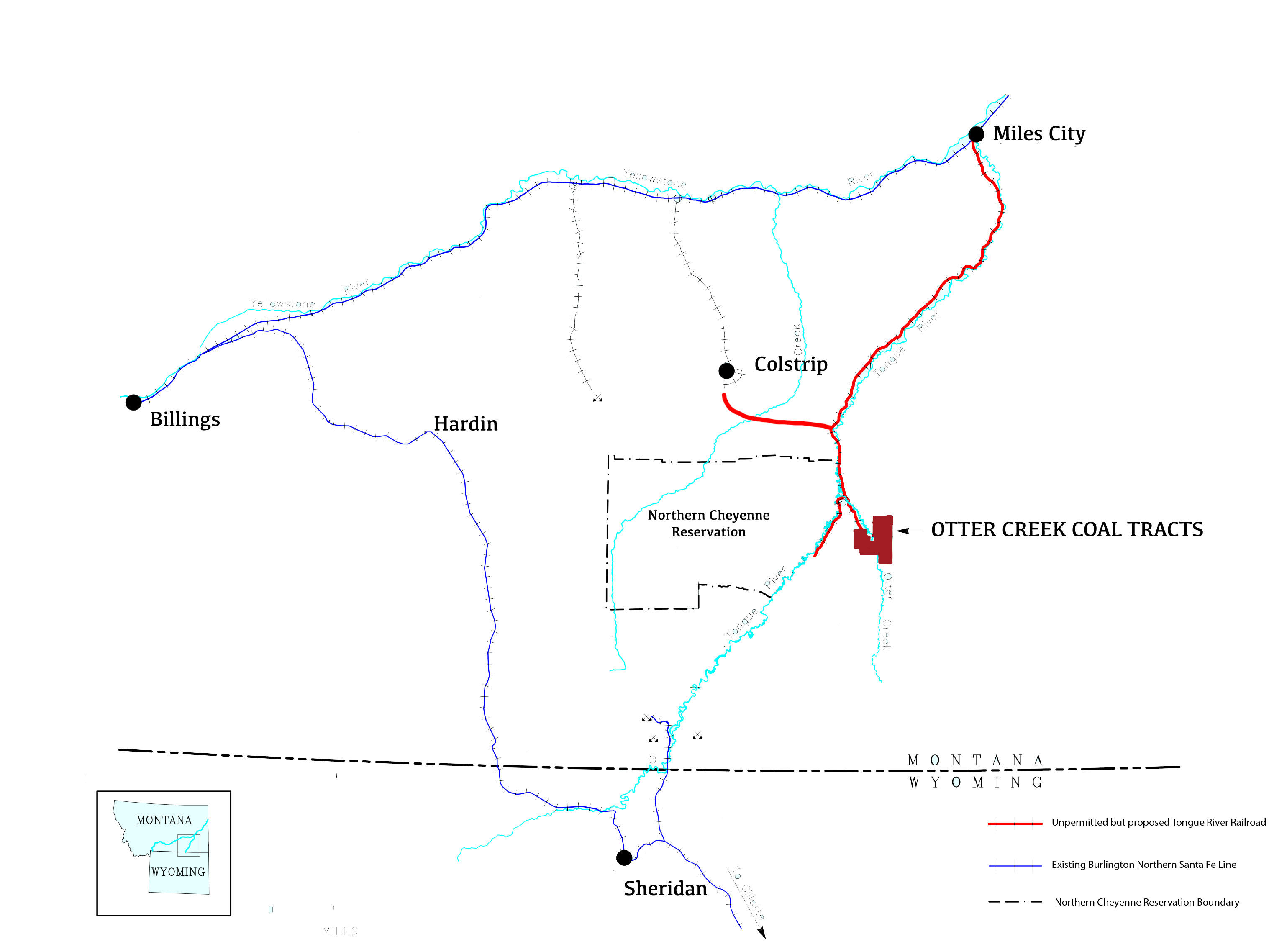

Montana Governor Marc Racicot: NO! We want coal tracts in southeastern Montana, specifically federal coal tracts in the pristine and agricultural Otter Creek valley.

[Enter Jim Mockler, Executive Director of the Montana Coal Council]Jim Mockler: Psst…Marc…come here for a second. Umm…you should really take the money. That coal would already be developed if it was economical. Take the money and run. Run Marc Run!

Montana Governor Marc Racicot: Shut up Jim. [Turns to Clinton] We want the coal tracts.

President Bill Clinton: Fine, I don’t like this but take the coal tracts.

[Meanwhile in southeastern Montana.]Northern Cheyenne Tribe: WTF! Seriously?

State of Montana and Department of Interior (under the 2nd Bush Administration): Yeah….

Northern Cheyenne Tribe: So, you protect Yellowstone National Park and we get screwed? Really???

State of Montana and Department of Interior (Bush Administration): Sorry but not sorry.

Northern Cheyenne Tribe: We’ll see you in court.

To be fair to Clinton, he tried to remove the transfer provision from the bill in a line item veto which was later overturned by the Supreme Court.

But, regardless, it happened. Faced with the prospect of massive coal development on its border, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe sued the Department of Interior to stop the transfer of the Otter Creek coal tracts to the state of Montana until their environmental, social and cultural concerns were dealt with. The Tribe stated in the complaint Northern Cheyenne Tribe v. Norton,

Development of the Otter Creek coal resources would impose severe environmental, socio-economic and cultural impacts on the tribe and its members.

The Tribe found it necessary to file suit to assure that its (mitigation) settlement effort would not be thwarted by an unannounced transfer of the tracts . The Tribe then agreed to dismiss the complaint, with prejudice, against Department of Interior with the signing of the Northern Cheyenne Settlement Agreement between the Montana State Board of Land Commissioners and The Northern Cheyenne Tribe on February 19, 2002.

Coming Up In Act II of Once Upon A Mine: Broken Promises and the Northern Cheyenne Settlement Agreement

* Major events, lawsuits and people have been completely ignored in my creative interpretation of events. And if you don’t like it, write your own play. I’ll publish it.

Liam, my two-and-a-half year old nephew ran up the stairs. Lena, my Border Collie was right behind him. I was a couple seconds behind her. When I got to the top of the stairs, they were staring at each other, Lena blocking the stairway.

Three seconds of eye contact.

One-thousand-one, one-thousand-two, one-thousand-three. I stepped around Lena and scooped Liam up.

“Don’t let Lena eat me.”

Lena sat down at my feet. I tried not to smile.

“Ok honey. I won’t let her eat you but you can’t go up the stairs without me, OK?”

“Ok.”

*****

Lena is just one in a long line of Bonogofsky dogs that have participated in babysitting. None as good as Blackjack, a big, awesome Doberman that didn’t let my sister or I out of his sight. Truth be told, he was much better than Lena because he actually cared about us. Lena sees my nephew more like a goat that needs to be herded, separated or stopped. She monitors his movements with a slight predatory look in her eye, glancing at me to see if I’m alarmed at his behavior.

Blackjack was always by our side. He went for walks with us. He herded us away from the creek. He played with us. He slept with us. He protected us.

When I was a kid, a couple of guys walked through our pastures and came up to the farmhouse. My mom, sister and I were alone. They were aggressive and belligerent, probably drunk. My mom told them to leave. The hunting dogs barked and snarled but Blackjack remained at my mom’s side. His hair was stiff along his back, his eye teeth bared. A low growl vibrated in his throat. Only my mom could hear it.

When they took a step forward, he took a step forward to meet them. When they took a step back, he took a step back. My mom wasn’t scared of them because she knew Blackjack had it under control. They were afraid that if they turned to go he would attack them. She told them he wouldn’t but what he would do was escort them off the farm. They turned to go and Blackjack followed them a quarter mile up a dirt road, on their heels, teeth bared until they hit the edge of our property. He stopped at the border and watched them until he couldn’t see them anymore and came home.

When he was eight, Blackjack died of dilated cardiomyopathy. It is a genetic disorder in Dobermans. His lungs filled up with blood and he drowned. He died in my mom’s arms on the way to the vet.

She still cries when she talks about Blackjack.

He was a damn good dog. One in a lifetime.

*****

Although Lena doesn’t have the same attachment to my niece and nephew that Blackjack had for my sister and I, she is attached to me. That means she is interested in what I’m interested in. When I’m with the goats, she feigns interest. When I’m babysitting the kids, she’s totally into it.

Fast forward a couple of months from the stairs incident to Christmas night. After the family gathering I helped my sister get the kids in the car. Liam was jacked up on new people and Christmas cookies and didn’t want to get into his car seat. I had the baby and couldn’t chase after him as he ran out into the dark farm yard. Lena watched him out of the corner of her eye and then looked up at me.

“Lena, get ’em”

She took off and within two seconds had blocked his route at the end of the driveway. He turned and started to head toward me and then broke off again away from the car.

“Lena, bring him.”

She was one step ahead of me. He ran three steps and she stopped him again.

Their eyes met.

One thousand one, one thousand two, one thousand three.

He turned and ran toward me and grabbed my legs. Lena trotted up and sat down at my side.

I looked at her and thought, she’s a damn good dog.

My sister and I and Blackjack.

Blackjack in the Beartooths.

Lena and I (2011)

“We don’t have a right to ask whether we’re going to succeed or not. The only question we have a right to ask is ‘what’s the right thing to do? What does this earth require of us if we want to continue to live on it?’” Wendell Berry.

If you want to understand the history and politics of coal in Montana you should read Last Stand At Rosebud Creek by Michael Parfit.

The book is about coal. It is about people. It is about power. It is a compelling and quick read. But what Michael Parfit couldn’t know when he wrote it back in the late 1970’s is that the Coal Wars did not end with the building of the coal fired power plant in Colstrip, Montana. He couldn’t know that almost 30 years later, we would be fighting a similar fight in the same country but this time with dire global consequences if we lose. He couldn’t know that the same people who had fought to protect their livelihood, their land and their water in the 1970s and 1980s, namely the Northern Cheyennes and ranchers, would be still be fighting the coal industry in their attempt industrialize the last best place of the last best place.

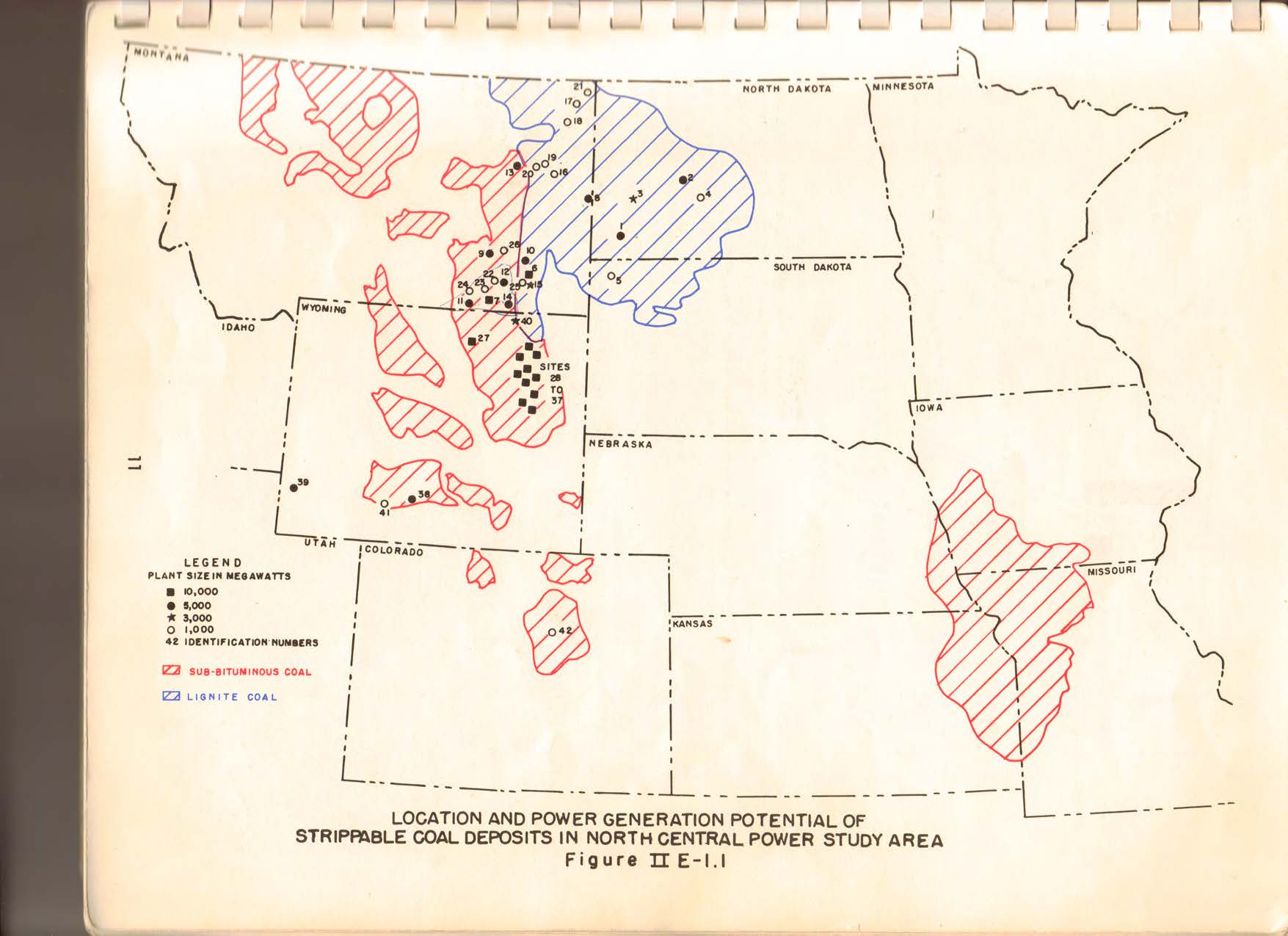

In 1971, the United States Department of Interior published a thick book called the North Central Power Study (NCPS). The NCPS forecasted that by 1980 the area would produce 50,000 megawatts of power generated by coal strip mines near each plant and by the year 2000, it would generate 200,000 megawatts, power to be sent both east and west. The power would be generated by 42 mine-mouth plants, most all of them in the Powder River Basin (as seen below in the NCPS map).

And as the saying goes, them’s fightin’ words. The publication of the NCPS galvanized the ranchers and the Cheyennes to fight for their land, their water, their culture and their livelihoods. Last Stand At Rosebud Creek tells their story through the eyes of 18 people.

“We know beyond a shadow of a doubt the Northern Cheyenne people, as with the gold in the Black Hills, as with the buffalo, so now with the coal in the Powder River Basin, are asked to offer ourselves up as the first sacrificial victims to this unwarranted invasion upon our land.” Bill Parker, Northern Cheyenne tribal member, 1974

I could easily summarize the book for you. About how the ranchers and the Cheyennes fought off the most extreme plans in the NCPS but also how they lost when coal fired power plant at Colstrip was built. But I’d rather you read it for yourself because it’s important to hear it from the people who fought then and are still fighting for their way of life.

The story told in Last Stand at Rosebud Creek isn’t done. We have proposals for new massive greenfield coal mines (Otter Creek) and new coal infrastructure (Tongue River Railroad) but we also have decision makers in the federal government who are continuing to lease out millions of tons of the public’s coal, completely ignoring the impacts of their actions on climate change and how climate change is already impacting our environment and economy. As Wendell Berry said, we don’t have the right to ask whether or not we will succeed.

There are a lot of old jokes about the code of the West. And it is true. There is a definite sense of propriety, and it is hard to explain, but there are things that you do and things that you don’t do. And that’s part of what we’re fighting for. We’re all convinced that the thing we’re doing is the right thing to do. But if we use the same tools that the energy companies use, then we’ve lost the battle. Because the rules they operate under aren’t compatible with openness and frankness and honesty, like we’re used to doing. People will come from an energy company and they’ll tell you something, and you’ll believe it. And hell, it’s not the truth; it’s merely expediency. And yet if we understand the situation and if we deal that way too, then most of the things we are fighting for, which is a way of life, are already lost.

There is a weariness in his voice, a weight of pessimism. Caught by that mood, I ask the natural question: Do you really think, given all the power, the money, the historical momentum that stands behind coal development, behind the power plant, that there is much hope of stopping it where it stands?

He studies his cigarette and stubs it out. A last small puff rises from the ashtray and dissolves gently in the air.

“Yeah,” he says eventually. “I think there’s a chance of stopping it.” His voice is still quiet, but it is quiet now because he seems to be restraining it, not because he is tired. His narrow eyes flick over to me again.

“Yeah,” he says. “I’m going to give her a whale of a fling.”

– Wally McRae, Last Stand At Rosebud Creek

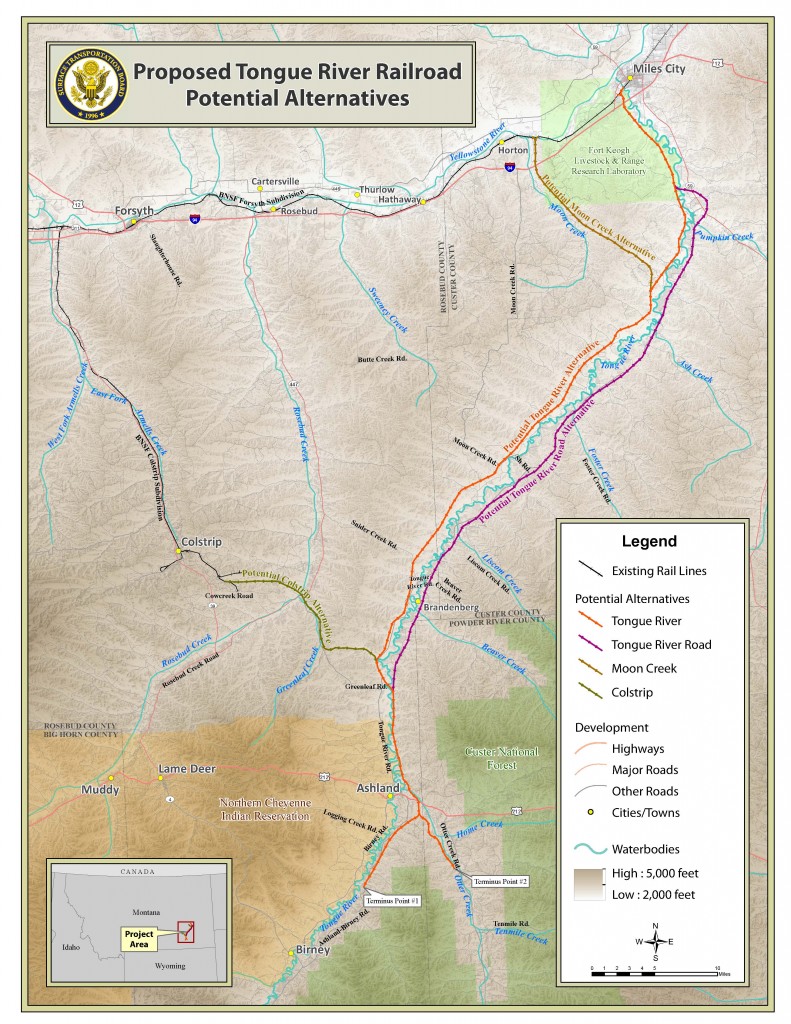

Those of you following the efforts of Tongue River Railroad Company to construct a coal rail line in southeastern Montana might be interested in a couple of quick updates.

1. The Surface Transportation Board is expecting to release the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) in late summer 2014. Earlier today, the STB held a Section 106 Historic Preservation conference call and Vicki Rutson, who runs the Office of Environmental Analysis at the STB, stated they expect to release the draft EIS in late summer 2014. She did make sure to emphasize that this timeline is subject to change. She also mentioned that the STB is taking this project extremely seriously and 1/3 of her staff is working full time on the project.

2. The Section 106* Consultation Meeting will be held in Billings, Montana on February 13 -14 and the Crowne Plaza. On a related note, the STB will be hosting a second in-person Section 106 Consultation Meeting with tribal, historic preservation, and conservation representatives in Billings. If you have any information regarding historic and cultural properties that the Tongue River Railroad may impact, this would be a good time to bring up your concerns or potential new information. If you cannot attend but would like something specific addressed, please contact me and I’ll make sure it is addressed at the meeting.

*The Section 106 regulations (36 CFR Part 800) require the STB to take into account the potential effects of the Tongue River Railroad on historic properties including: historic buildings, prehistoric and historic archaeological sites, artifacts, traditional cultural properties, and landscapes (both tribal and historic).

3. Review of the public testimony from 2012. As we move into the EIS process a bit further this year, I think it is good to remember what was said by the local folks (Northern Cheyenne and landowners) that will be impacted by the Tongue River Railroad at the STB Scoping Hearings held in November of 2012 in southeastern Montana. You can watch a short compilation video I put together at the beginning of this post. If the video above did not load correctly on your browser, you can reload the page or click here to see it directly on Vimeo. Thanks to Jeff King for recording the hearing.

Also, if you want to dig into the project details even more, the STB has a Tongue River Railroad project website with all the documents, maps and historical information.