And Yet We Have Changed

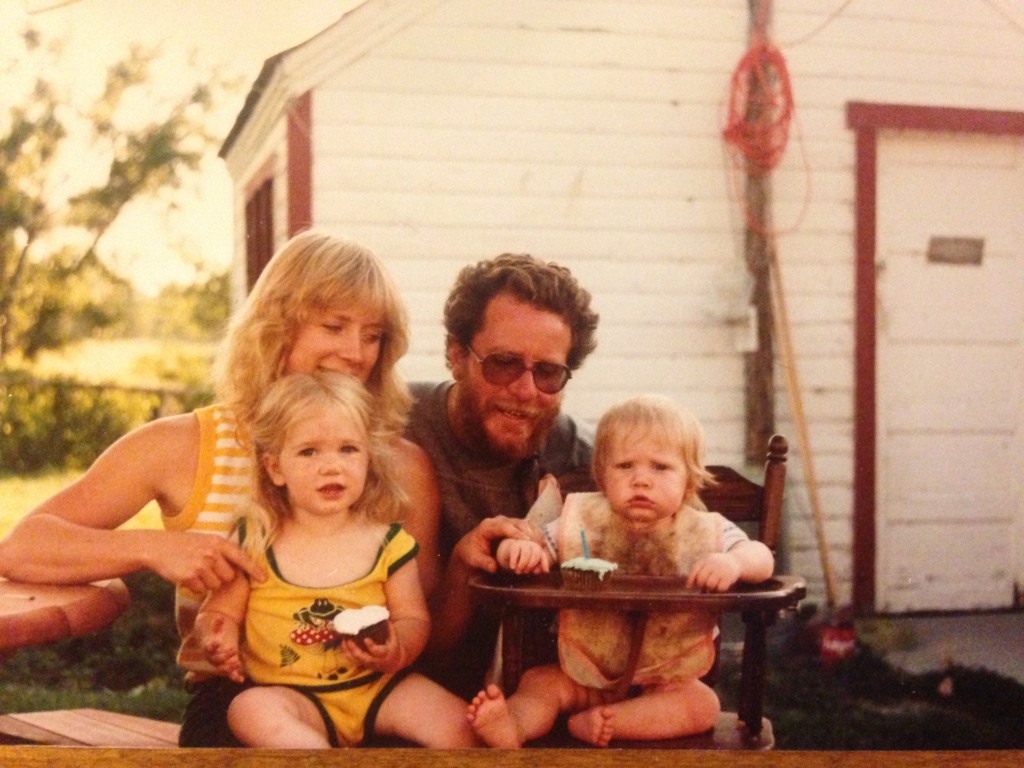

I walked in to my dad’s garage last weekend and hit the power button on his stereo. The Doors sang Break on Through and the volume was all the way up. I stood at his workbench and listened until Jim Morrison finished the last chorus. I closed my eyes and for a moment I pretended he was outside fixing a broken down piece of equipment. When he worked on our farm he turned on the stereo in the garage as loud as it would go, opened all the doors in the shop and then wandered around listening to something else in his AM/FM stereo headset, singing along poorly with no regard for the correct lyrics.

Everything in his garage is still mostly where he left it. On his workbench sits a dusty old wagon night-light he was always meaning to fix for me when I was little. There is also his antique watch repair toolkit, the tennis balls he would take the felt off of so it wouldn’t wear the dog’s teeth down when they played fetch, his meticulously organized tool drawers with handwritten labels, his bike tire pump that he had since he was a child, pocket knives, Strike Anywhere matches and an old tin of Prince Albert.

He was so particular about his stuff. This is a trait I did not inherit. I have his long toes, the Bonogofsky nose and his stubbornness but not his need to keep things in order. I borrowed fencing pliers. He found them on the back of the four-wheeler and a 20-minute lecture followed. Did I change my behavior? Nope. Instead, for example, one time I bought a new pitchfork and left it down stuck in the goat’s round hay bale. He took it out and put it in the shed, “where the pitchforks go.” It was a constant battle between us. I bought it, I could ruin it if I want to, I told him. Now that he is gone, I use his tools and put them back exactly where he kept them.

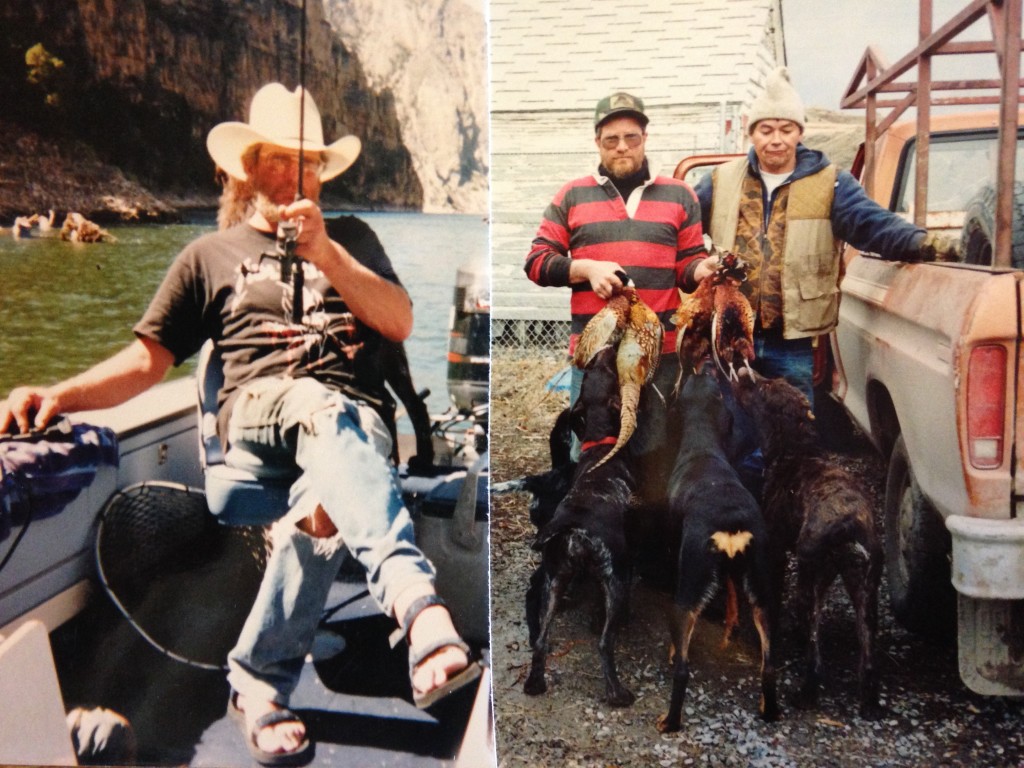

My dad loved his dogs. He sat on the couch, sharing a pint of ice cream off the same spoon with his hunting dog Max. You were lucky if you only had to listen to one or two stories of the epic retrieves Max completed in his hunting career. A dog that good deserved ice cream from a spoon he said. I helped him dig many graves in the dog cemetery near the top slough on our farm. We dug each hole deeper than we needed to, just to be safe, and piled Yellowstone River rock on top of the grave that we hauled up. For each one he wept. When Maggie, my hunting dog, died last month I know he would have cried for her too.

I look around the old farmhouse, that I grew up in and live in now, and I see him. I see him sitting on the kitchen chair trying to unlace his work boots while the dogs swarm around him licking his face. I see him standing over the stove frying up deer steak on a Saturday afternoon after work. I see him getting up in the dark early morning hours of winter to go on a service call or to plow snow.

The other day I was deleting old voicemails from my phone and I realized that the last one my dad left me on the day he died was gone. I wanted to hit my phone with a hammer. Instead, I cried all night.

I remember what he said though.

“Why don’t you ever pick up your goddamned phone?”

A moment of silence and then,

“Well, I guess I don’t pick mine up much either. Call me back.”

I called him back and we talked about smoking brisket for my friend’s wedding. I wanted him to come down to the farm to help me and he said, “you know how to do it honey, you don’t need me.”

I can’t say how it is for other people, I can only say how it is for me, but I find no reason to pretend to have a stoic courage about my father’s suicide. I have no words of wisdom about losing someone you love. Life is harder without him. I search for something that will make sense but my need for meaning comes up against a wall of reality that will not budge no matter how hard I push.

But, if I’m being honest, I feel like I’m not doing something right. I’m not remembering him right. I need to remember more. I need to remember exactly but exactly doesn’t exist. The one thing I remember perfectly is how tight he used to hug me, sometimes so tight it was hard for me to breathe.

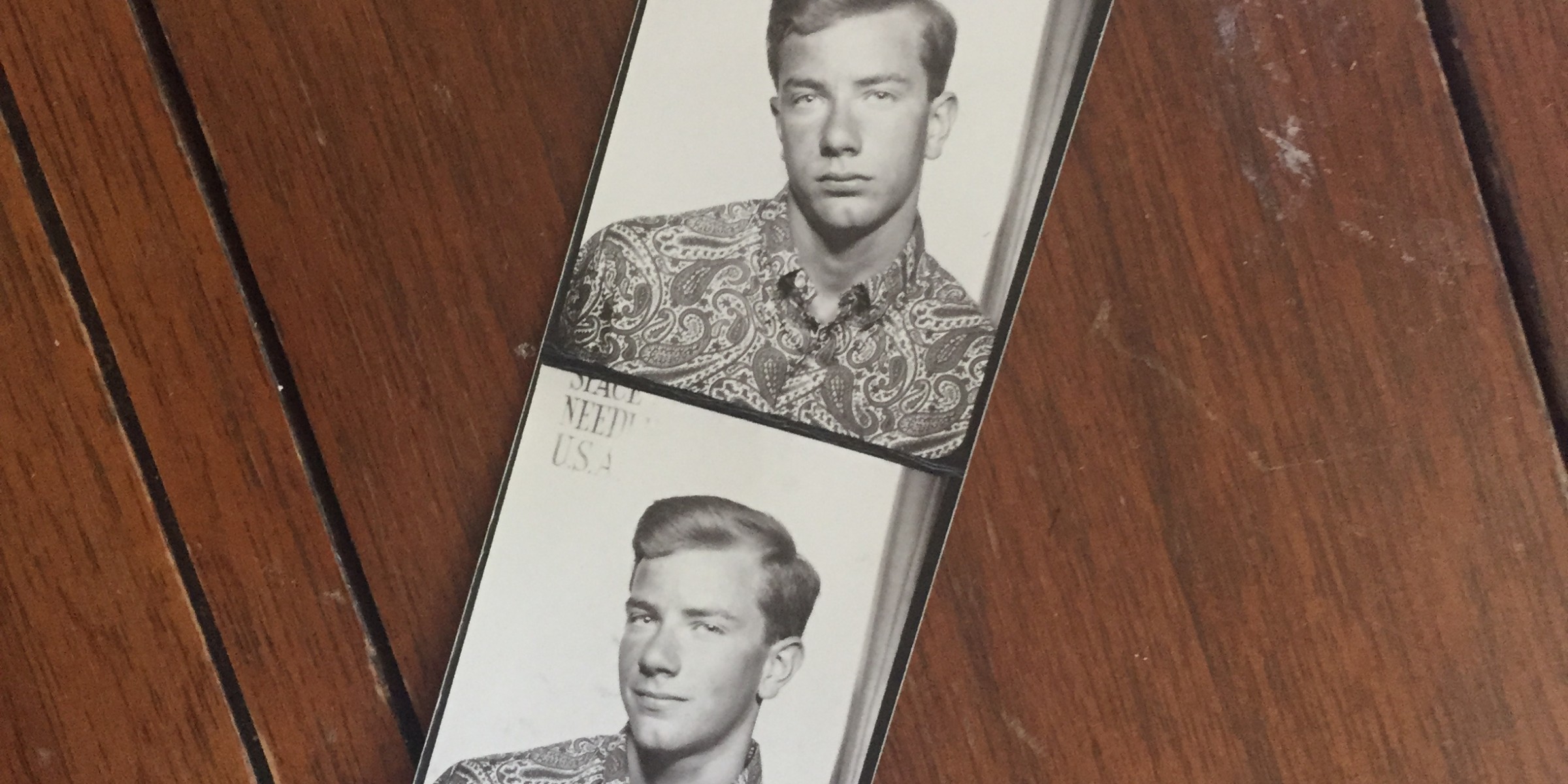

When I write about my father, what I fear isn’t that I’ll tell you too much, it is that I’ll tell you too little. How do I take the complicated person that my father was, or more accurately, my experience of who my father was, and reduce it to fragmented memories and feelings and ideas? He deserves more. As Walt Whitman so eloquently put it, he contained multitudes, so do we all. His story is inevitably my story. Who he was to me reflects who I was then and who I am now. But I am a different now. I am changed and now my memories of him have a different meaning than they used to.

How can the death of one person feel so enormous?

In the most important way I am blessed. I know my dad loved me. He knew I loved him. In the end, what more can we hope for than to be able to express our feelings to the people that we love and have those feelings be reciprocated?

The poet Rilke writes best about what sits in our hearts after a loved one dies in Letters to a Young Poet.

“Great sadnesses … they are the moments when something new has entered into us, something unknown; our feelings grow mute in shy perplexity, everything in us withdraws, a stillness comes, and the new, which no one knows, stands in the midst of it and is silent. I believe that almost all our sadnesses are moments of tension that we find paralyzing because we no longer hear our surprised feelings living. Because we are alone with the alien thing that has entered into our self; because everything intimate and accustomed is for an instant taken away; because we stand in the middle of a transition where we cannot remain standing. For this reason the sadness too passes: the new thing in us, the added thing, has entered into our heart, has gone into its inmost chamber and is not even there any more, — is already in our blood. And we do not learn what it was. We could easily be made to believe that nothing has happened, and yet we have changed, as a house changes into which a guest has entered.”

Alexis, my dad died in 1984 and I too still remember his hugs! You will not forget that feeling ever!! Love ,Bonnie

Still missing my amazing father, Dr. A.W. Elting, a Miles City veterinarian, rancher and teacher. He was my hero…

Hey Alexis, my dad committed suicide too. There are more of us out there than it seems, sometimes. Very nice post.

Alexis, I found your blog through my friend Steve Gilbert, and brother Greg Tollefson, both long-time friends of the Tongue River country. Another brother died a month ago, and your writing about your father resonates deeply. Thanks for sharing your thoughts, and your gifted voice.

Val Tollefson

Alexis, I know you don’t know me, but your father was a wonderful friend and businessman of ours. We exchanged butchering recipes and I would take him some homemade noodles on occasion. He would come and borrow the chicken plucker from us. We shared many stories and laughter together over the years. He will greatly missed. I lost my husband Ron, in 2011,so I know what your going through. With God and family we some how get through it all,but will never forget them. God bless you and your family. Cherryl

Beautiful. Touching. I never had a father. Certainly no hugs to remember, although we had two conversations., – once while he was here in body, and once while he was in spirit. Wishing you some sweetness from the love he poured into you.

Beautifully written. When you wrote:

“But, if I’m being honest, I feel like I’m not doing something right. I’m not remembering him right. I need to remember more. I need to remember exactly but exactly doesn’t exist.”

That reminds me of a line from Norman Maclean’s Young Men and Fire:

“It is the frightened and recessive grief suffered for one whom you hoped neither death nor anything evil would dare touch. Afterwards, you live in fear that something might alter your memory of him and of all other things. I should know.”

May the cherished memories of your father give you relief in your grief.

Beautifully written, Alexis.