****UPDATE: 2/24/2017

I have some leftover calendars and so I’m selling them for $5.00/calendar + $5.00 flat shipping rate. PayPal button has been updated with new pricing!

If you have any questions please email me at abonogofsky@gmail.com

*******************************************************

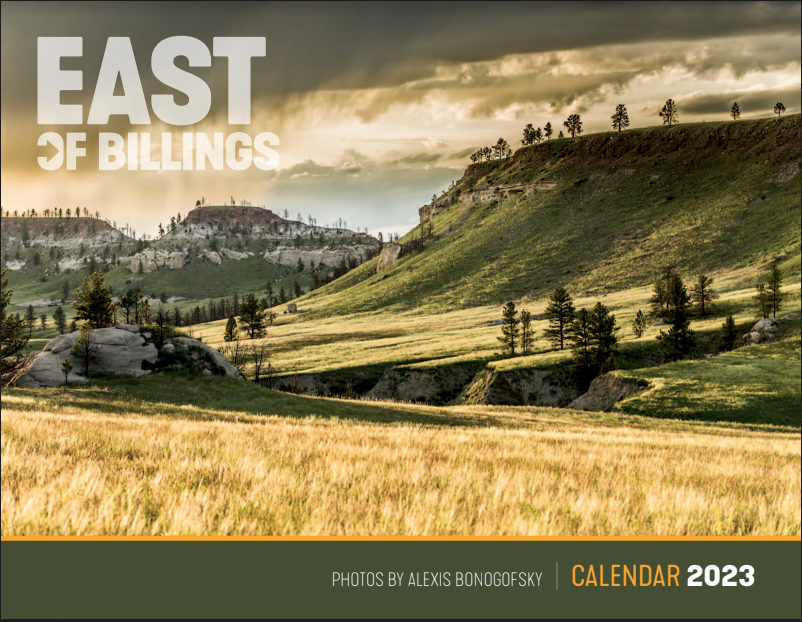

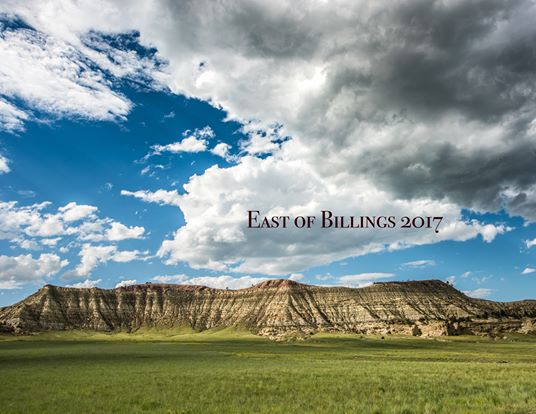

The calendar is 8.5 x 11 in full-color with thirteen of my favorite photographs of southeast Montana.

$10.00/calendar + $6.50 shipping.

Here are the ways to get your calendar:

1. Paypal:

If you would like to pay by credit card online please click on the Buy Now button and follow the instructions provided by PayPal.

It’s a funny story really. I was never that interested in hunting. I always thought it was something that the “boys” did. But then, one day, I was at a sporting goods store with my man. He was looking at guns (yawn) and talking with the salesmen about calibers, gauges, loads and other stuff I really couldn’t care less about.

I was posting a selfie on Instagram and was waiting for the likes to start rolling in and someone ran into me while I was staring at my phone (how rude!). I looked up to scowl at the person and it’s lucky I did because I saw something that would change my life forever: pink camouflage.

Hunting wasn’t just for men, it was for me too! All it took was a corporation to understand my needs, make the product and then charge twice as much for it as men’s hunting clothes.

All it took was the color pink.

How could I feel like a woman in army green and dull pukey yellows. Ugh. Or, even worse, orange? Even just a little bit of pink on the clothes makes me feel more like a woman while I’m hunting. Underneath it’s all pink camo lingerie. (It’s so comfortable when you’re hiking around and you can still feel sexy while you’re elbow deep in deer guts..am I right ladies?) And, don’t even get me started on pink camo guns. Thank god they make them. There are so many guns in the gun department! It’s confusing.

The color pink is like a homing beacon for my vagina.

Honestly, I don’t need hunting clothes that fit me or really any other options. I need clothes that are made in a color that has been arbitrarily assigned to me because of my gender. Recently I’ve been reading about how legislators in some states are making blaze pink legal for hunting. It made me feel, I don’t know, like someone really understands what motivates me to pick up a rifle and kill an animal for food.

Getting up early (I have to get up even earlier than the men so I can put on my makeup), in the cold, stalking an animal, taking its life, gutting it, hauling it out and then spending a couple of days butchering it just wasn’t something I was willing to do before pink camouflage came along.

Critics might argue that this is all just a marketing strategy by corporations to sell more stuff and that the people who introduced the blaze pink legislation are completely stereotyping women and are out of touch with why most women hunt. And, sigh, they would also probably say that the time, energy and money spent on these pieces of legislation would be better used for outdoor skills workshops for people who want to learn how to hunt. Whatever.

Critics be damned.

I, for one, understand that if anything, hunting is just another opportunity to be a consumer. Hell, just slap that pink on whatever you want us ladies to do and we’ll be there, no questions asked.

It’s official. The proposed Tongue River Railroad is done.

Today the Surface Transportation Board issued a decision officially ending the Tongue River Railroad. On November 25, 2015, the Tongue River Railroad Company had asked the STB to hold the application in abeyance, which means they wanted the STB to suspend work on the permit application but keep the docket open until the proposed Otter Creek mine received a permit from the state of Montana.

On Earth Day, April 22, 2016, the Surface Transportation Board met and decided to deny the Tongue River Railroad Company’s (TRRC) request to keep the docket open, officially ending the entire proceeding at the STB.

Today, on April 26, 2016, it was officially announced.

If you want to get into some details, here is a brief timeline of what happened with the legal proceedings leading up to this decision.

On December 11, 2015, shortly after the TRRC asked for their application to be suspended yet remain open, Northern Plains Resource Council and Rocker Six Cattle Co., who have legal standing in the proceeding, filed a motion to deny and dismiss with prejudice the TRRC’s application. Dismissing with prejudice means that the TRRC could never come back to the STB with another permit application for the project.

Then, on January 15, 2016, TRRC filed a notice stating that Arch and Otter Creek Coal filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. They argued that the bankruptcy didn’t affect the status of the mine permit or the rail construction application.

On March 10, 2016, TRRC filed a supplement to its petition stating that Arch Coal was suspending their efforts to secure a mine permit from the state of Montana. The company continued to maintain that the permit application in front of the STB should remain open.

Northern Plains and Rocker Six responded on March 15, 2016 arguing that Arch Coal’s decision to suspend work on the mine permit application was even more evidence that the STB should dismiss the Tongue River Railroad permit application.

On April 5, 2016, TRRC responded stating that Arch Coal still possessed a lease from the State of Montana for the coal tracts and that energy markets can change quickly.

On April 15, 2016, NPRC and Rocker 6 responded stating that over half the coal tracts are leased from Great Northern Properties Limited Partnership, and that that entity terminated the lease months ago.’

On April 22, 2016, the STB met and decided to dismiss TRRC’s application without prejudice.

“We will deny TRRC’s request to hold this proceeding in abeyance and instead dismiss the proceeding without prejudice. At this time, there appears to be little prospect that Otter Creek Coal’s mine permit will be secured in the foreseeable future. Otter Creek Coal and its parent, Arch, have both filed for bankruptcy, and Otter Creek Coal has suspended its application for an MDEQ mining permit indefinitely. While it is possible that Otter Creek Coal or another party could restart the mining permit application process in the future, it is unclear whether and when this might occur. Therefore, to keep this docket open would serve no purpose.”

Today, as I was doing research for an article I’m writing about bottled water and Nestlé, I came across a photo of a dead young Albatross with a stomach filled with plastic. To be exact, it was twelve ounces of plastic and it died because, obviously, its intestinal system couldn’t process it. That basically sent me into spiral of nihilism that almost compelled me to head to the local bar at noon.

This is relevant because I am sitting in a wonderful little town in west Texas, thousands of miles away from my friends, family and my dogs, feeling slightly out of place and uncertain of my surroundings. Feeling lonely, combined with trying to write about something in which being bombarded by the world’s problems courtesy of the internet, is very much a de-motivator.

Let me take a step back.

There are wonderful, energetic students from the Wild Rockies Field Institute that camp on my farm every year as part of their trek across Montana to learn about energy issues. Besides the fact that I keep getting older and they stay the same age, I love having them there. We tour the farm and I show them where the 2011 Exxon oil spill was and introduce them to the goats and the mean rooster named Chicken. We talk about coal mines and railroads, oil spills and pipelines and the relationships between the government and corporations and where the public fits in, or doesn’t.

In the end, they always ask me versions of the question, what can I do? It is one of the only questions I hesitate to answer. It’s too big and abstract. I don’t do abstract. I look behind me for someone that knows what they’re talking about but usually it’s just my border collie Lena playing with a stick trying to get their attention.

For people who work in advocacy and public interest, that question might seem easy to answer; get involved and make your voice heard. Do what you can, where you are at. Learn about the issues. When I hear those things all I hear are vague generalities that most people have a hard time connecting with.

I have a hard time answering their questions because I have the same feelings all the time. Does what I do matter? Do my individual actions make a difference to all of these massive problems that are causing the suffering of life everywhere? Whatever social or environmental problems there are, what I do know is that they are probably connected and you could spend your life trying to fix them. That, combined with the sheer number of issues and complex interactions between them, can be paralyzing and not just for people starting out.

When I do try to answer the question, my mind races around like a ping pong ball and jumps from vague to specific things; be kind, don’t buy bottled water, listen, get to know people who aren’t like you, don’t be a dick, pick a place and save it, try not to be judgmental, stop staring at your phone, don’t lecture people (no one likes that), call your Senator, call your Representative, call your City Council member, and on and on. Did I say be kind and stop staring at your phone? And what am I talking about? I never call my Representative.

I’m pretty sure that I say something different every time.

I am making myself write about it because I need to understand what is really being asked and because I don’t know the answer to the question. I hope through the process of writing and talking to others about it I can find a little bit of clarity myself.

So instead of writing what I’m supposed to be writing about, I’m writing about writing about it. I have no argument or conclusion or profound realization.

I’ll start again tomorrow.

By now the demise of the Otter Creek mine is old news.

I thought I should write something about it but I didn’t. Talking to a good friend a couple weeks later, I told him that it felt weird to write, photograph, organize and spend a significant amount of my life and emotional energy on something and then let the end of it pass without a note or retrospective. He told me that I’ve already written everything I needed to. He was right. I was content to sit back and just let myself be happy that it was over.

And yet there will probably always be something more to say because the struggle in southeast Montana taught me bigger lessons about community, about politics and about people.

In March of 2010, when the state of Montana leased the coal tracts to Arch Coal, most people were convinced there was nothing to be done. Once the coal was leased the issuing of permits seemed inevitable. As we all know government agencies aren’t in the business of denying permits. However, during those six years, the Otter Creek mine and Tongue River Railroad never received a permit, not one.

Sometimes the distances between southeast Montana and Helena felt insurmountable. I’m not sure the people who held the fate of the valleys in their hands really understood that the core resistance to this project didn’t stem from an attachment to a certain political ideology or from outside environmental groups.

The resistance came from local people who held wildly different political views but all cared deeply about a place. That is why we won. It’s that simple. Hundreds of people, who cared nothing about credit, attention, money from donors or environmental politics, spent their time and their own money to involve themselves in our democracy. You can’t sustain six years of grassroots opposition and public involvement if the people don’t truly care about the place they are trying to protect.

For many in Helena and Washington D.C., southeast Montana and the proposed mine were abstractions. They weren’t personally connected to the place so it made the Otter Creek valley just words on a map, a place for mining. That bureaucratic abstractness made it hard for them to understand or care that the issue was the very real destruction of a real place that would impact real people.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot since the Livingston Enterprise ran an editorial last year entitled, “There is a place for mines but it isn’t on Emigrant Peak.”

That phrase lodged itself in my brain; a place for mines. I’m not politically naive. I recognize the usefulness of the tactic, but, as someone who works and lives in an area that others think is a place for mining, I also recognize the enormous damage that it does. The sentiment was echoed in a recent opinion piece about the proposed gold mine exploration near Yellowstone National Park by a local business leader. It reads,

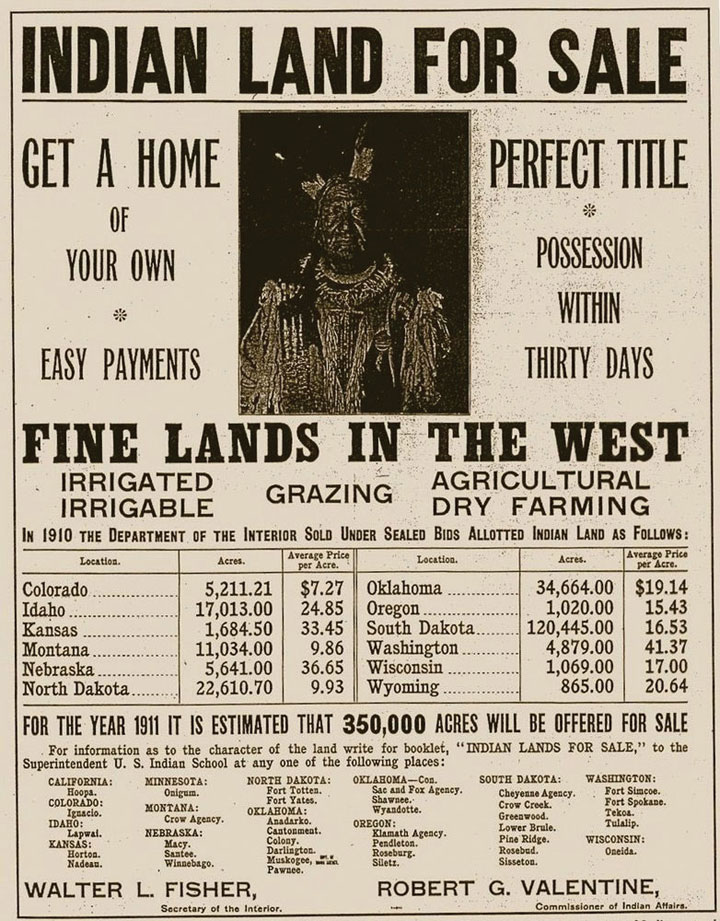

Lest we forget how the Otter Creek mine happened. In order to protect the greater Yellowstone ecosystem from a gold mine, taxpayers paid a Canadian gold mining corporation $65 million dollars and federal lands in other places to give up their mining claims around Yellowstone National Park. Later, taxpayers spent another $8 million from the Land and Water Conservation Fund to finish the purchasing of the land from a private owner. To appease the Governor of Montana, who argued we were losing out on revenue and job creation, the federal government transferred the Otter Creek coal tracts to the state of Montana. Although there were those that spoke out against the trade and tried to stop it, it still happened. Not many people were willing to spend political capital on the Otter Creek valley, a place for mining.

What could we accomplish together if we stopped treating our working landscapes differently than, what Wendell Barry calls, the ‘gated communities of the wild?’ We must recognize the value of protecting our working landscapes, like the Otter Creek valley, as much as we recognize the value of protecting the great wild lands of our state, like the greater Yellowstone ecosystem. The places that we love, and we all have them, are connected. Water, air and wildlife don’t recognize human created boundaries.

We must guard against, in our actions and our words, myopic strategies that have real consequences for other places. Are there communities “better suited” to large scale industrialization and mining? Who gets to make that determination? How will this new fight to protect the greater Yellowstone ecosystem end?

Rarely do local communities have a choice in the matter, rather it is imposed upon them by corporations and governments. Large scale industrialization, and the associated environmental and human health consequences, usually happens in places that don’t have the resources, political and financial, to fight back. This is the type of thinking that leads to sacrifice areas.

Ground zero is the in the eye of the beholder. Some projects are more disastrous than others depending on your position in time and place, both geographically and financially.

We don’t gain anything by breaking up Montana into places for mining and places for protecting. That doesn’t build community. That doesn’t build power.

Lucky for all Montanans, the people working to protect the Otter Creek and Tongue River valleys succeeded by traversing that space that exists between communities, cultures, political ideologies and landscapes.

They made a place for protecting.