I don’t want to write about human shit. I really don’t. There are hundreds of other things I’d rather write about and should be writing about. But I feel compelled because the last couple of years, while hunting, I came across five piles of human shit right next to or directly on public land parking areas.

Huge piles of people shit.

Sometimes there were unnecessarily large wads of toilet paper on top of the piles. Sometimes I’d see long strands of toilet paper with brown streaks flying off over the prairie grass, getting hung up on sage brush.

When I first considered writing about this topic I thought I might go in to detail about my shitty experiences, but I think you can probably imagine what it is like. If you’ve spent any time in the woods, you’ve most likely had similar ones. Be thankful I didn’t include photos of these finds. Although, to the people whose shit I found, I might offer a piece of unsolicited advice: eat better food.

These piles of shit, although the most disgusting and most memorable, are not the only things I’ve found scattered about our public lands when I’m hunting. There is a type of public land user who seems to think our shared landscapes – places that were set aside for wildlife, recreation and the nourishment of our soul – are a dump. People who think these places exist only to be used how they see fit and treated carelessly.

I find empty beer cans lying in my path. I find old bike helmets, used condoms, candy bar wrappers, energy drink cans, empty shotgun shells, used hand warmer packets, toilet paper and, of course, human shit. Sometimes I find animals that someone has killed and left lying – proving to his buddies what a man he is. I find ruts and tracks where people drove in places they shouldn’t have.

In my walks through the prairies and the woods I never fail to find the evidence that this type of public land user has preceded me.

I doubt anyone who treats our public lands like this can be reached through an ethical appeal. Although, I do point to these experiences when hunters complain about some private landowners not allowing public hunting.

The stories I’ve heard from ranchers would make any ethical hunter cringe in embarrassment.

This may seem like a small problem to some readers compared to the current threats to our public lands; selling them off, shrinking the boundaries of protected areas, impacts from climate change, and our current Interior Secretary’s fetish with energy dominance.

The list goes on and on.

To me though, all the threats, including trash on our public lands, come from the same mentality. They come from the person who thinks public lands are only places to be used, places to extract from, places for more and more consumption, whether the prize be game, oil, coal, gas or timber.

I was struck by a passage out of Wendell Berry’s essay A Native Hill. And it made me think some of what our public lands need is not more owners, but more friends.

“The false and truly belittling transcendence is ownership. The hill has had many owners, but it has had few friends. But I wish to be its friend, for I think it serves its friends well. It tells them they are fragments of its life. In its life, they transcend their years.”

**Photos of trash provided by a friend to our public lands, Nancy Anderson Porter.

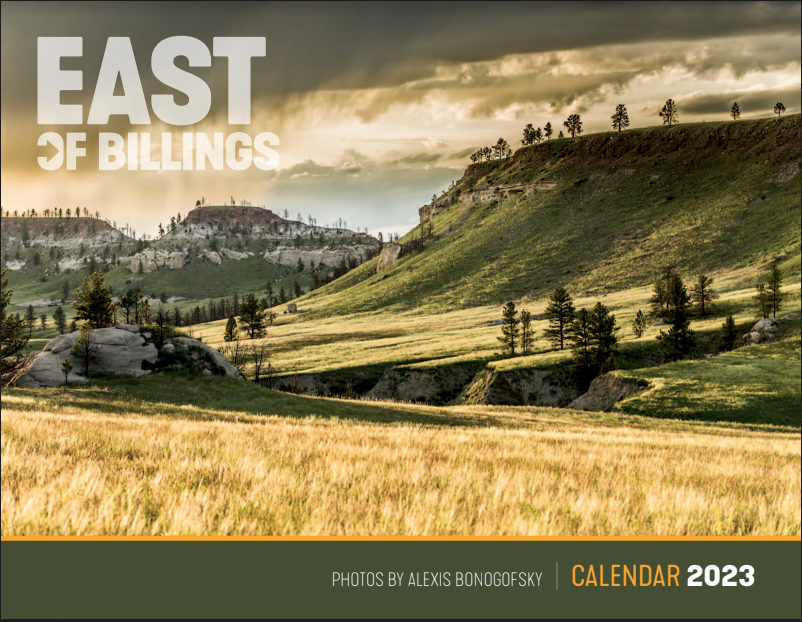

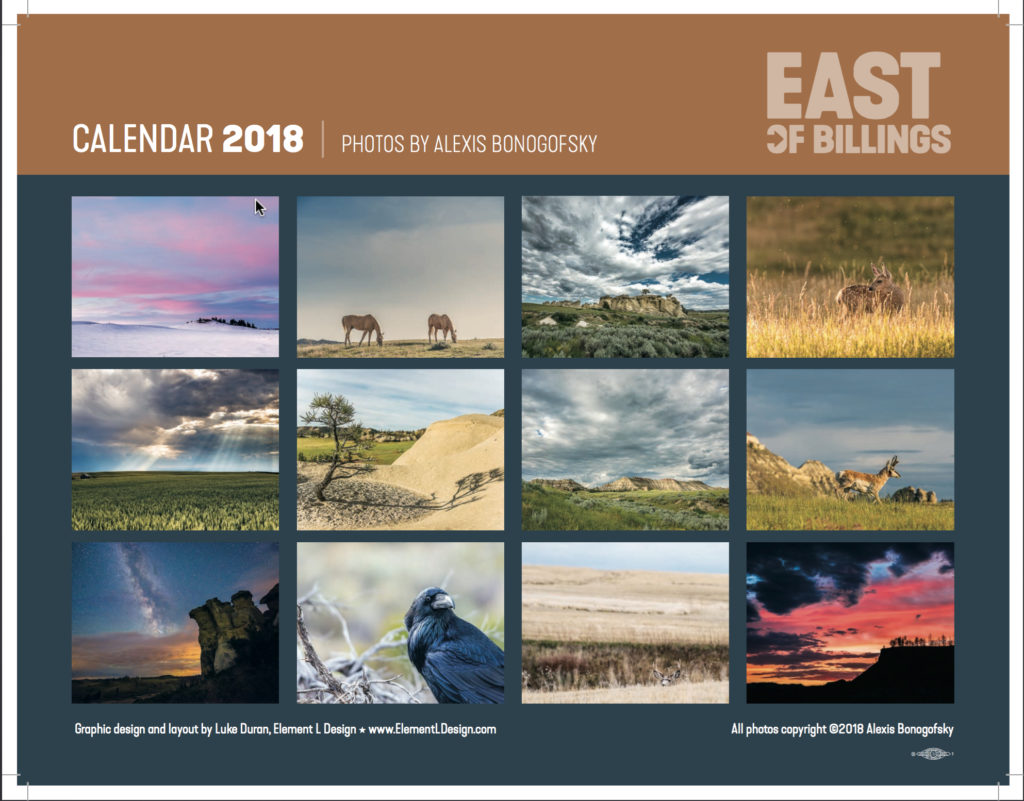

The 2018 east of Billings calendar is ready to order. The calendar is 8.5 x 11 in full-color with some of my favorite photographs I’ve taken this year in eastern Montana. You’ll see big landscapes, big skies, big sandstone rocks, and some iconic eastern Montana wildlife. This year the calendar is designed by a talented graphic designer out of Helena, Luke Duran, who also is the photo editor for Montana Outdoors magazine.

Important note: I won’t start shipping the calendars until December 1st. If you need them shipped faster than 2-3 day priority shipping, please send me a direct message.

The cost this year is $15.00 per calendar + $6.65 USPS priority flat rate shipping.

Here are the ways to get your calendar:

1. Paypal:

If you would like to pay by credit card online please click on the Buy Now button and follow the instructions provided by PayPal.

2. Check

If you would like to pay by check, you can send a check made out to me, Alexis Bonogofsky, 2020 Tired Man Road, Billings, MT 59101. $15/calendar plus a flat $6.65 shipping rate. Once I receive the check, I will put the calendar/s in the mail.

3. East of Billings ArtWalk Show on December 1, 2017

I have a show at ArtWalk Billings on December 1 at the Downtown Billings Alliance at 2815 2nd Ave N, Billings, MT 59101 from 5 – 9 p.m. You can come by there to pick up the calendars and see the rest of the show. We’ll have beer and wine and music by Ed and John Kemmick!

As always, I appreciate your support!

Alexis

Young willow trees slap me in the face as I weave my way through the island. I can’t see more than two feet in front of me even with my headlamp on. I’m tripping on dead cottonwood branches and occasionally stepping into pools of water. I have cockleburs in my hair, stickers in my legs, and my stomach is growling.

“F****** goats.”

If you think it would be fairly easy to find a whole herd of goats in a relatively small area even at night, you’re wrong. You don’t know anything about goats. They don’t care about you or your life or what you have to do the next day. They do what they want.

I am down on my hands and knees, belly crawling through a particularly dense area of vegetation. I’ve gone too far to turn back and try to find an alternate route. Lena, my border collie, has tried to abandon me twice already. It is 9:00 p.m. on a Monday and we have been looking for the goats for over an hour and a half.

When the water is low on the Yellowstone River during late summer and early fall, a large island near our farm becomes accessible to livestock. It’s a jungle: willows, cottonwoods, Russian olive, tamarisk, woody debris piles – all packed in as tight as can be. The goats hit the island hard in the fall, going straight for the leafy spurge and the other noxious weeds they love.

Tonight, they didn’t come back to the barn. Ungrateful bastards. I take care of them: feed them, doctor them, make sure they have a good life and they repay me with a late night trek through a river bottom.

I know this island. I have played on it since I was a kid, following the game trails, swimming in the river and exploring, but right now, in the pitch black, it feels unfamiliar. I can’t see any lights that would help orient me besides the red flashing radio antennas that I occasionally glimpse through the trees. Walking through the willow trees is disorienting and I feel like I’m walking in a circle.

The movie the Blair Witch Project pops into my mind. It doesn’t seem out of the realm of possibility that I am about to stumble upon an old cabin with a crazy witch in a corner waiting to kill me. It would be the goats’ fault and I bet they wouldn’t even care.

As I exit the willows onto a sandy beach I hear a loud KABOOSH. It sounds like a large person doing a cannonball into a pool. I look over and see a dark mass moving through a small side channel of the river. It’s a very angry beaver. Lena runs to the edge of the water with her ears up.

“Sorry Mr. Beaver,” I say. I turn and head west.

KABOOSH!! It’s louder this time. I quickly turn, feeling like he is right behind me and he is. He sensed victory as I retreated down the beach and he swam as close to me as he could for one more “f*** you” tail slap. I think about the fisherman in Belarus who was bitten to death by a beaver, and all he was doing was trying to take its picture. Ok, so no Blair Witch death for me; Death by beaver bite it is. Still I’m sure the goats won’t care either way.

We walk. We walk some more. We get on the four-wheeler and Lena sits on my lap. We drive up and down the river. Raccoons are up in the Russian olive trees eating the berries. Owls fly by carrying tiny rodents. And the goats, well, the goats are probably bedded down chewing their cud, most likely somewhere fairly close to me, but they’ll stay still and quiet because they’re assholes. I’ve probably already walked by them numerous times.

A plus is that no one has called yet to tell me my goats are in their yard or running wild in the nearby trailer park. Not that that has ever happened before. There is one neighbor whose number I have programmed in to my phone whose first name is “the goats are out,” and last name is, “stop whatever you are doing and pick up the phone now.”

We give up and go home. I worry about them all night. There are a couple old does with the herd and it wouldn’t take much for a coyote to take them down. But they are goats, not sheep, which means they try to avoid death, not run towards it.

The next morning we find them bedded down next to one of the sloughs in a place I didn’t think to look the night before. As we walk up to them some of them stand and stretch in the sun and others keep snoring, oblivious to our presence.

This is how the conversation went.

Me: Hey!

Goats: (sleep)

Me: (louder) Hey!! Do you know what you put me through last night? I was looking for you for hours.

Goats: (shrug)

Me: Seriously, you are all really lucky that one of you isn’t dead.

Goats: (stretch)

Me: Well, are you gonna follow me or what?

Goats: (chew cud)

Me: Will you please follow me?

Goats: (look up)

Me: Pretty please?

I lure them with a fresh branch off a cottonwood tree to show them the path back to the gate they need to go through. They love cottonwood leaves so they begin to follow me slowly, unsure if I can be trusted. Twenty feet from the gate the smallest doe, and the leader of the herd, sees a part of the fence where ground dips, making more space than usual between the bottom wire and the ground.

If you think a full grown goat is not able to fit under a six inch gap between the ground and wire, you’re wrong. You don’t know anything about goats. They don’t care about you or your life or if you have time to fix fence that day. They do what they want.

I turn just as the little goat sticks her head under the wire and begins to belly crawl through.

Me: The gate is right here. You can’t walk an extra 20 feet?

Goat: (continues to belly crawl)

Me: Seriously?

I watch as the entire herd, all of whom are two to three times the size of the little goat, follow her underneath the fence.

Me: F****** goats.

Once upon a time in land not so different than our own there was city built along a mighty iconic river with towering mountains to the west and never ending prairie to the east. It was the largest city in the state.

During one of the waning days of summer a council of citizens, who were elected by the residents of the city to make decisions for the good of the people, gathered for their weekly meeting. They had an important decision to make: whether or not to allow medical marijuana shops to open within their fair city.

Citizens came in droves and lined up to speak. Many gave heartfelt and compelling testimony about the ways medical marijuana improved their quality of life, helped them kick opioid addiction, and made cancer treatment bearable.

And then one man stood. We shall call this man Jeff. Jeff ran an organization in a nearby town that protected the citizens of the state from imaginary things. We shall call this organization the Family Foundation. Jeff was nervous but he steeled himself for his testimony.

He thought, “If not now, when? If not me, who?”

Jeff walked up to the podium and cleared his throat. He told the council that he knew a man, a man who lived in a city not so far away, who had trouble selling a commercial building because it was next to a medical marijuana dispensary. He paused for dramatic effect.

“The smell,” he said, “we have to consider the smell.”

“Nailed it,” Jeff thought to himself, with a little fist pump he hoped no one noticed.

Some members of the council solemnly nodded as he spoke. “Yes,” they thought, “Jeff makes a good point, we must consider the smell. The residents of our town should not be asked to smell the smell of weed if they don’t want to smell the weed. And what if someone at some point is a little inconvenienced when they try to sell their commercial building?”

“How much can we ask of this community,” they thought?

As the council considered the wise words of Jeff, outside, there were three nearby oil refineries along the banks of the mighty river. Occasionally, or maybe frequently, those refineries flared off some gas and stuff, the smell of chemicals and sulfur so ubiquitous that most citizens didn’t notice it anymore. The smells of the refineries were famous throughout the state.

Jeff continued. He spoke of the evils of the marijuana. It is a gateway drug. It is addictive. Addiction is bad, said Jeff. If you allow this, you, the government, are encouraging an addiction.

As the council members considered the evils of addiction, thousands of citizens were in one of the 127 casinos playing at one of the 2,229 gaming machines within the city limits. These citizens weren’t at the council meeting — because they were gambling — but that’s only because they were certain that the council was looking out for their best interests. They weren’t addicted or anything. Also, in this community, there were 82 painkiller prescriptions for every 100 people.

One council member thought about the stiff whiskey he was going to have when he got out of this interminably long meeting.

Jeff went on.

“Marijuana tears at the moral fabric of our society,” he said. “It destroys families. And the children, he said, we must protect the children.”

As the council members considered the moral fabric of their society, outside there were around 30, maybe a little more, maybe a little less, “spas” and “massage parlors” in this town. They were open 24-hours-a-day, 7-days-a-week and were located all over town; on main roads, in shopping centers and one was even across from a local high school. The windows were darkened and the neon lights never shut off.

These spas were places where men, no matter their standing in the community — doctors, lawyers, politicians, truckers, mechanics — could go and pay for a hand job, or maybe a blow job or maybe even sexual intercourse with young Asian women whenever they wanted. Ride your bike or park your car a little bit down the street and throw on a hat and you’re good to go.

Many of these women have their passports taken, their visas confiscated and are forced under the threat of violence to have sex with strange men. They are moved around to keep them uncertain and scared about their surroundings.

These women are slaves, they are the face of human trafficking.

If a man had enough money, he could buy a 14-year-old girl for $900 for the first hour, $800 for the second and if he wanted to keep her for three or more hours, the price keeps going down.

But this story is coming to a close boys and girls. In the end, seven out of the eleven council members determined it was in the best interest of the community not to allow medical marijuana shops within the city limits. And we were all saved, oops, I mean the people of this imaginary city were all saved from a smell of marijuana and most importantly, the horrendous impacts of people feeling better by smoking or eating pot if they have cancer or another disease.

Jeff was pleased. He could now focus all of his efforts on making people scared of transgender people. Don’t thank him though, he’s just doing his moral duty to the citizens of this state.

The end.

If you want more information about human trafficking and what you can do to help, you can start with the Polaris Project.

At 5:30 p.m., on a frigid winter night in January of 2013, staff from the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and Arch Coal employees arrived at the tribal government building in Lame Deer on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation to hold a public hearing on the scope of study for the environmental impact statement for the proposed Otter Creek coal mine.

To get to the front entrance they had to walk by 150 Northern Cheyenne tribal members, off-reservation white ranchers and a handful of environmental allies from around the state huddled together around a small fire. Otto and Martin Braided Hair drummed and sang Northern Cheyenne traditional songs.

The DEQ, like many government agencies these days, decided to host an “open house” instead of a public hearing. An open house is when the agency sets up a couple of booths and individuals walk around from table to table and ask questions of agency staff. Then, if you have a comment, you walk to a secluded part of the room where a court reporter is sitting. It’s awful.

In a real public hearing, the community has an opportunity to hear each other talk about the impacts of a project and ask questions. You learn from what others are saying. It sparks ideas. It helps you understand other’s viewpoints. In an open house people are isolated from each other. There is power in public hearings and they are foundational to democracy. I love them. All of them. If I could go to public hearings every day I would.

I was hooked the moment I read this paragraph in Last Stand at Rosebud Creek,

“This was their moment of decision: a public hearing may not have much effect in the halls of legislation, but it uncompromisingly defines the motives and emotions of a community and, even more clearly, the beliefs of the individual. You speak; you make yourself known; you are no longer a bystander in conflict.”

Open House or Public Hearing?

At 6:00 p.m. the open house was supposed to start but no one from the public was inside the tribal building. The DEQ staff was starting to get a nervous. They walked outside and told us that if no one came in they would close down the meeting and leave.

Shortly after that announcement the assembled group followed Tom Mexican Cheyenne, the designated speaker, into the tribal building. We brought our own microphone and speaker system. Tom politely informed the DEQ and representatives from Arch Coal that we would have a real public hearing and they were welcome to stay and hear what the community thought about the proposed coal mine on the nation’s borders.

Here’s what Tom said.

“I have been asked to be the spokesperson for our people here who are wanting to express what they see is happening in southeastern Montana. And first of all I want to welcome our visitors. The people that have come from Helena and other places and probably the company that is planning on doing the development here. We are here as people from southeastern Montana and also as people who have relatives and ancestors who passed on and gave their lives and their family’s lives and their children’s lives for this land. Just about a week ago we had a run from Ft. Robinson, NE to here. Young people running in memory of our ancestors that didn’t want to stay in Oklahoma anymore and wanted to come back to their homeland. We consider southeastern Montana, this area here, as our homeland even though we don’t physically own it on paper which is the way you look at the ownership of land. We don’t own any land, when we leave this earth, we don’t take it with us, it stays here. But we also believe we take care of it.

We heard about what you did in Broadus and Ashland, how you set up stations and I just want to say that when you come here, you are coming to where we live and I’m going to ask you that you respect that. We don’t talk to microphones, we talk to people. We want our people to be able to hear what is being said and this is the way we’d like you to conduct this. We want our people to tell you how they feel about what you are planning on doing here, in this country.

This is the way we’d like it to be done. Because we have elder people here and other people who have something really important to say that needs to be heard by everybody and not just one microphone and one individual sitting here switching it on and off. We don’t want that to happen here and we want you to respect our ways. This is why we are here.”

A two hour open house turned into a five hour public hearing.

At the end of the evening, Brad Sauer a white rancher from off the reservation stood up to the microphone.

“I want to say to my neighbors the Northern Cheyennes thank you for showing me what free speech looks like and sounds like.”

The crowd cheered.

What can we learn from this story?

If you take my recounting of this event at face value, you might assume I’m saying people should take over public hearings. If you think that, you’re wrong. One of the big problems with sharing this, a story previously was unknown to most people, is it is just one small piece of a extremely large puzzle.

It doesn’t teach you much unless you know the larger strategy and story behind stopping the modern iterations of the Otter Creek coal mine and Tongue River Railroad.

On that cold night in January, in the middle of what most people would think of as “nowhere,” 150 people showed up for their land and community. It was a night where people took a little control back from our government and industry.

However, this action wouldn’t have made sense if we hadn’t already been participating in the government process for the previous five years. We were all commenting, attending agency meetings, lobbying politicians, reading hundreds of pages of documents, holding events and making sure we knew what was happening. We had been building support for years and making sure that when we did something like this that we knew we could pull it off. We weren’t worried that it wouldn’t work. It wasn’t a social media stunt. It wasn’t for random attention, it was to show the state of Montana what they were up against; a community was united and we weren’t going to let them push us around.

We were showing Arch Coal that it was hostile territory.

This story is about a tactic but it can’t be separated from the larger strategy. The work east of Billings teaches me that real organizing is about building relationships between people and not always about numbers and that the most impactful organizing is not general and national but specific and local. It is about developing a long term strategy for particular goals and being resilient. It’s about working with people who feel accountable to each other and not about name-calling and exclusion.

Organizing isn’t just about getting people to protests and rallies or signing petitions (even though sometimes those are important tactics), it is about helping people become competent leaders in our democracy.

One is transactional the other is transformational.

Why now?

Why am I telling this story now? Because I’ve realized the only way we can continue to move forward is if we share our stories about winning and losing, about what works and what doesn’t, about the nuances of organizing work. You never get that information from a lot of organizations so people looking to become more active in government don’t realize what it takes or where to start. You don’t see a lot of people who are part of campaigns or groups talking about the failures.

Just wait till I get to those.

There are a lot of interesting lessons that can be learned from eastern Montana and from great organizers in the rural west. What does it look like to have a people from different backgrounds, cultures and political views working together for a common goal? How does it happen? I certainly don’t have all the answers, in fact, I don’t have any. But I have ideas.

I’ve been hesitant to share these stories before because organizing is about personal relationships and therefore when I write about it I am inevitably dragging a lot of people along with me whether they like it or not. To help alleviate my anxiety about this, sometimes I will write in general terms to protect my relationships and my friends from unwanted attention and sometimes in very specific terms when it’s appropriate.

I’m going to write about what worked, what failed, the good that comes out of failure, what frustrates me about where I see organizing work going and where I’d like to see it moving. I’m also going to share some stories and insights from other rural organizers I admire and books organizers should be reading.

And if you, the reader, find anything that is helpful in what I’m writing then I’ll consider this effort worthwhile.

Welcome to the EOB organizing school.